This is one of the most heartbreaking and upsetting narratives of lynchings in American history that we have had to report during our time as a platform.

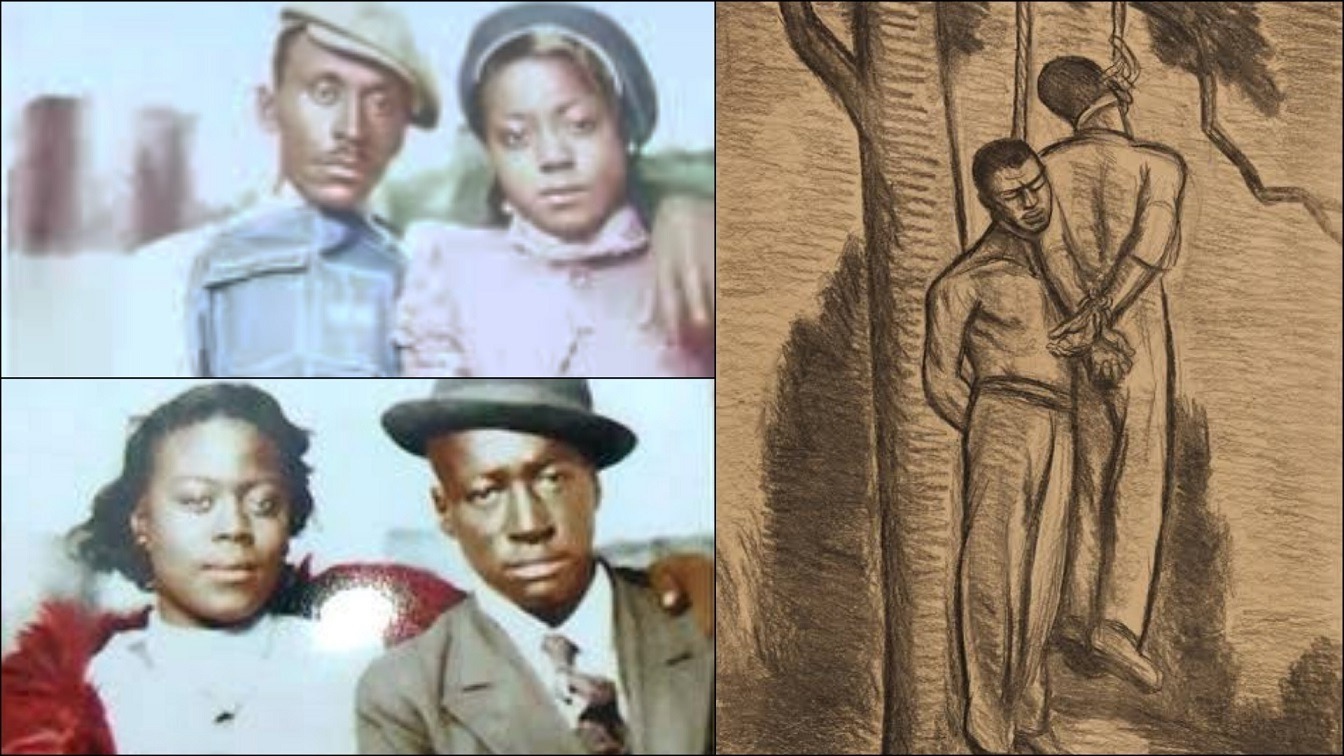

This is a harrowing description of how four African American sharecroppers were killed on July 25, 1946, near Moore’s Ford in northeast Georgia. The event is now known as “America’s last mass lynching.” The murderers of George Dorsey, Mae Murray Dorsey, Roger Malcolm, and Dorothy Malcolm were never apprehended.

The event’s violence and public uproar mirrored the expanding African-American challenges to Jim Crow in the post-World War II years, as well as local and federal authorities’ failures to address racial inequity and violence in the South.

A fight between Roger Malcolm and his wife Dorothy precipitated the issue in Walton County, about sixty miles west of Atlanta, in mid-July.

Local authorities detained Malcolm on July 14 after he stabbed white overseer Barnette Hester, who had intervened in the domestic conflict. Dorothy Malcolm and Hester may have had a sexual relationship.

J. Loy Harrison, a white farmer, drove Dorothy Malcolm and fellow sharecroppers George and Mae Murray Dorsey to the Monroe, Georgia, jail to bail free Roger Malcolm on July 25, eleven days after the incident.

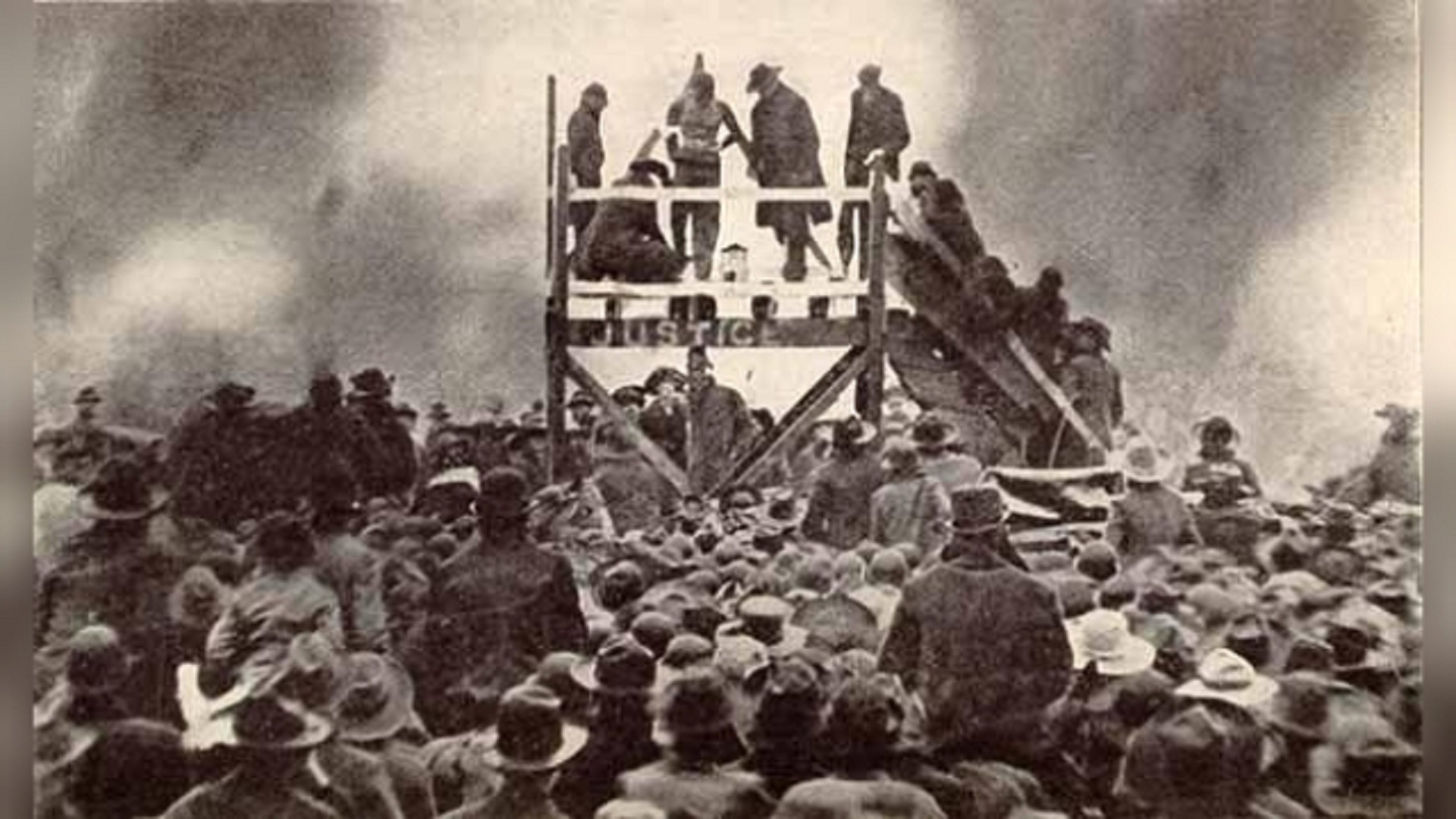

A big white mob halted Harrison and the two couples on their way back near the Moore’s Ford Bridge on the Apalachee River.

What happened next sparked heated dispute among Harrison and other witnesses. Loy Harrison, like many others who congregated at Moore’s Ford Bridge, was said to be a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Finally, the sharecroppers were beaten before being tied to a tree and shot to death. Dorothy Malcolm was seven months pregnant when George Dorsey, a World War II veteran, returned from combat in the Pacific.

The attack’s public nature drew national media attention. In Georgia, lame-duck Governor Ellis Arnall, who had recently been defeated in a bid for a second term in the 1946 Democratic gubernatorial primary race due to his limited support for African American voting rights, urged the Georgia Bureau of Investigation to assist local authorities in the hunt for the killers.

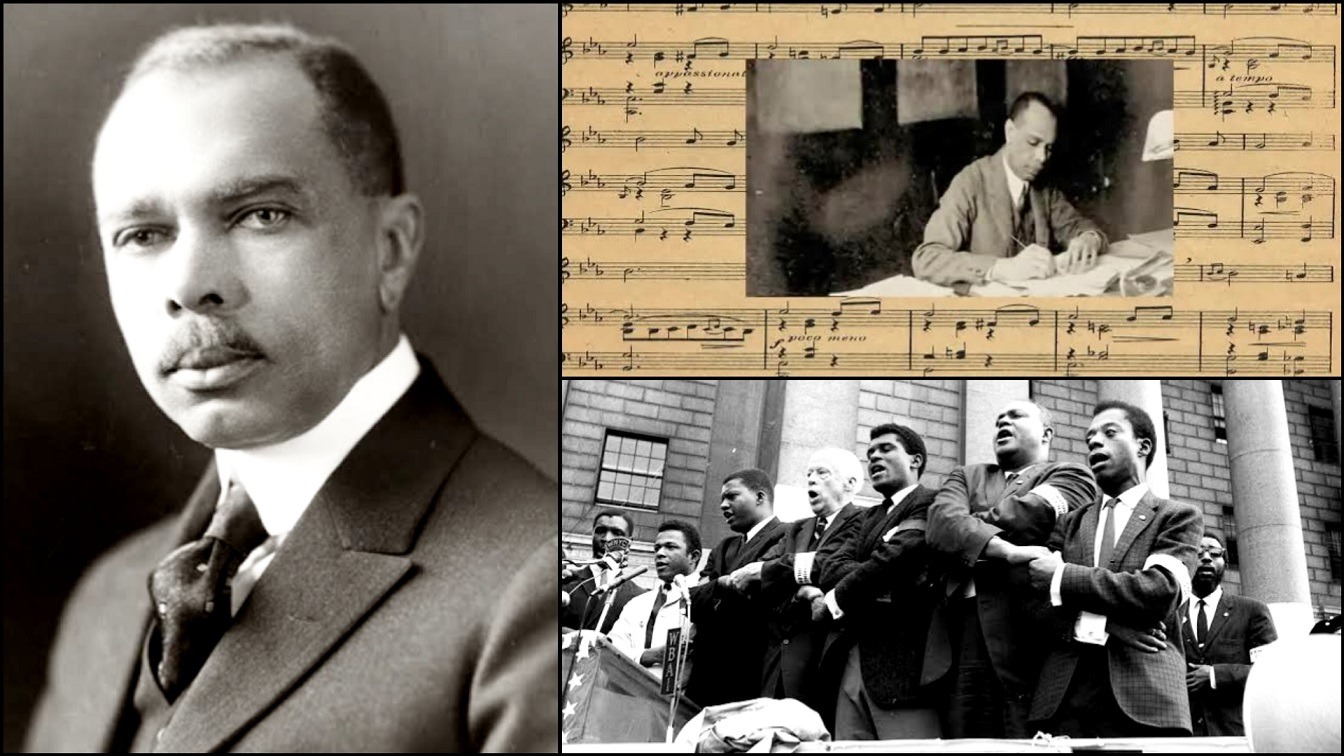

Leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) raised public awareness of the crime in order to compel the federal government to take action.

Finally, United States President Harry Truman announced a $12,500 prize for information and authorized the Federal Bureau of Investigation to investigate the matter.

The Moore’s Ford lynching influenced Truman’s decision to form the President’s Committee on Civil Rights and integrate the military in 1948.

Despite these actions, no one was prosecuted for the crime perpetrated at Moore’s Ford. Despite the fact that at least fifty-five people were claimed to have participated in the mob action, FBI investigators retrieved shell casings and bullets from the tree where the four sharecroppers were executed and discovered no witnesses willing to testify as to the identities of the offenders.

Walton County held a grand jury hearing to hear evidence about the crime, but no indictments were issued. The NAACP used the case to promote an anti-lynching bill in Congress, frustrated with the lack of justice and other reports of violence against servicemen returning from World War II, but membership in NAACP chapters across the South dropped in the 1940s out of fear of retribution from the KKK and white mobs, as well as the state’s white power structure.

Renewed interest in Georgia’s civil rights battle in the late twentieth century drew attention to the Moore’s Ford lynching. Bobby Howard, a civil rights leader, collaborated with the NAACP in the 1960s to revive efforts for justice in the case.

In 2004, the Georgia Bureau of Investigations and the FBI returned to the case, questioning numerous now-elderly witnesses and conducting more forensic investigations. These investigations have mostly been stymied because witnesses have remained silent regarding the Moore’s Ford occurrences.

Although no convictions have been obtained as a result of the investigations, continued local efforts keep the Moore’s Ford lynchings in the public eye. In 1997, an interracial group of Walton County residents formed the Moore’s Ford Memorial Committee to build a historical marker at the bridge site. Since 2005, public re-enactments of the lynchings have become an annual ritual in the region.

When we write about these atrocities against our people, the world wants us to forget and move on, the same world that hasn’t stopped sobbing about the Jewish Holocaust.

They want to remember Hitler’s genocide, but they won’t let us recall the African holocaust, which is still going on now.

We disclose these atrocities so that our people will regard our ancestors’ memories with more respect, knowing full well what they went through to maintain our bloodline – our heritage.

Fathers and mothers should teach this to their children so that they understand what happened to their forefathers and can recognize such behavior in today’s world.

Our forefathers paid the ultimate price for our freedom today; all they ask is that you remember and share their stories with those around you.

We will triumph!

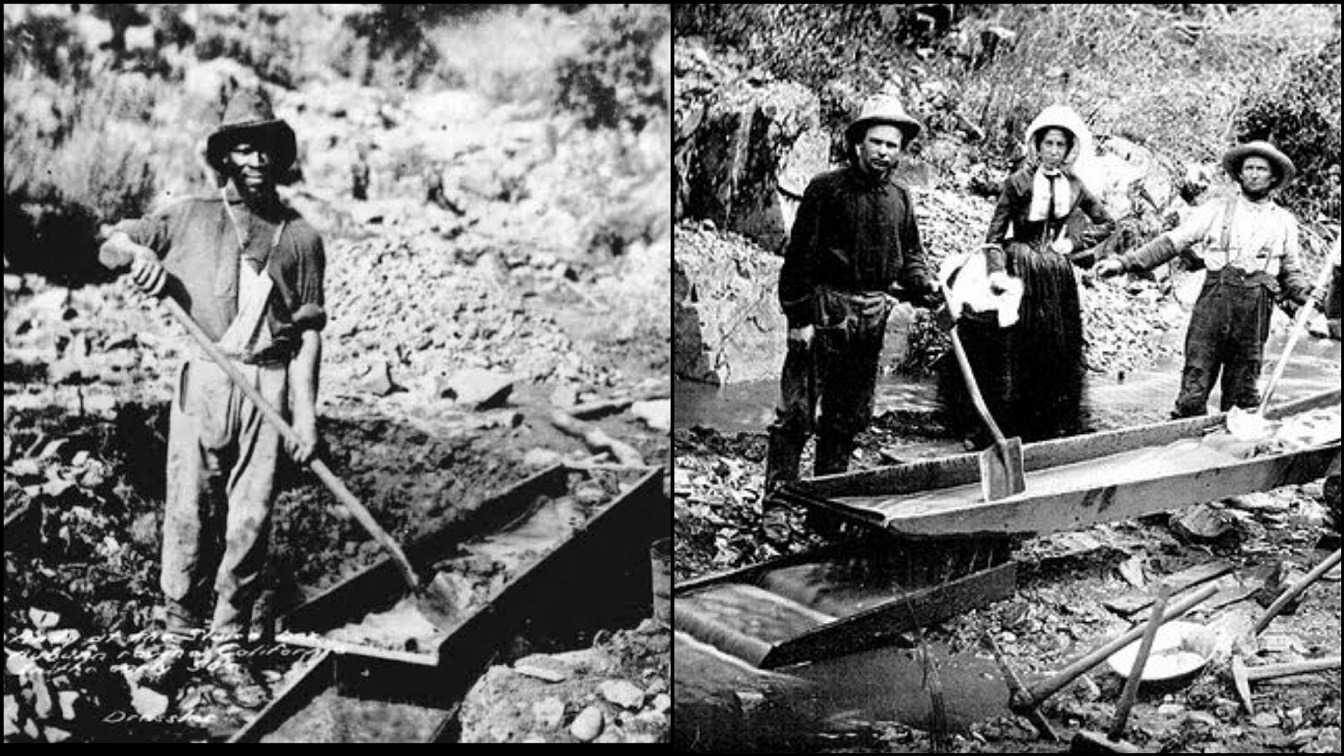

Please use Google to discover photographs of this report in History. We have been prohibited from exhibiting photographs of gory and disturbing scenery.