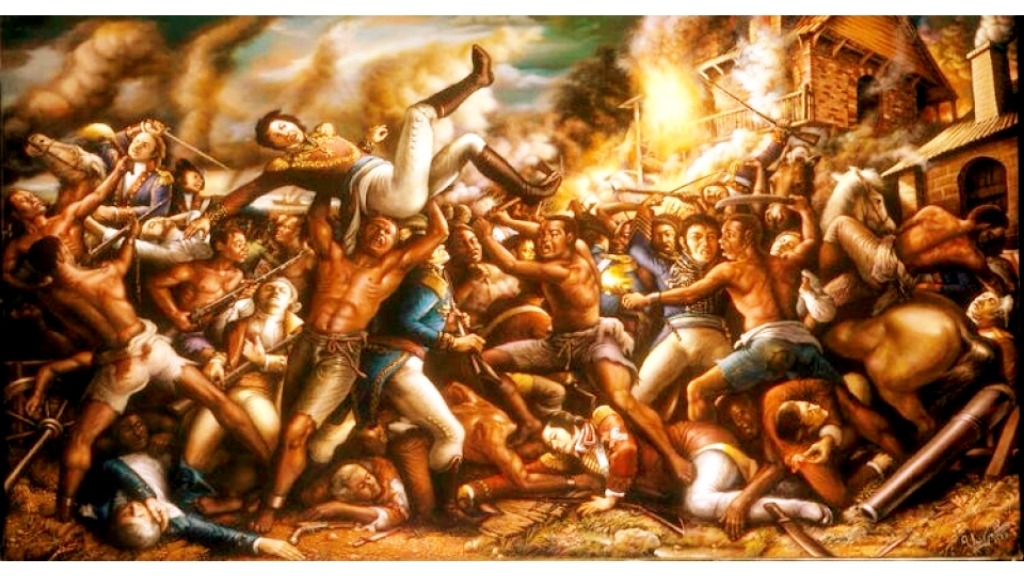

Brown University’s Kona Shen outlines in detail how voodoo played a crucial part during the Haitian Revolution in History of Haiti:

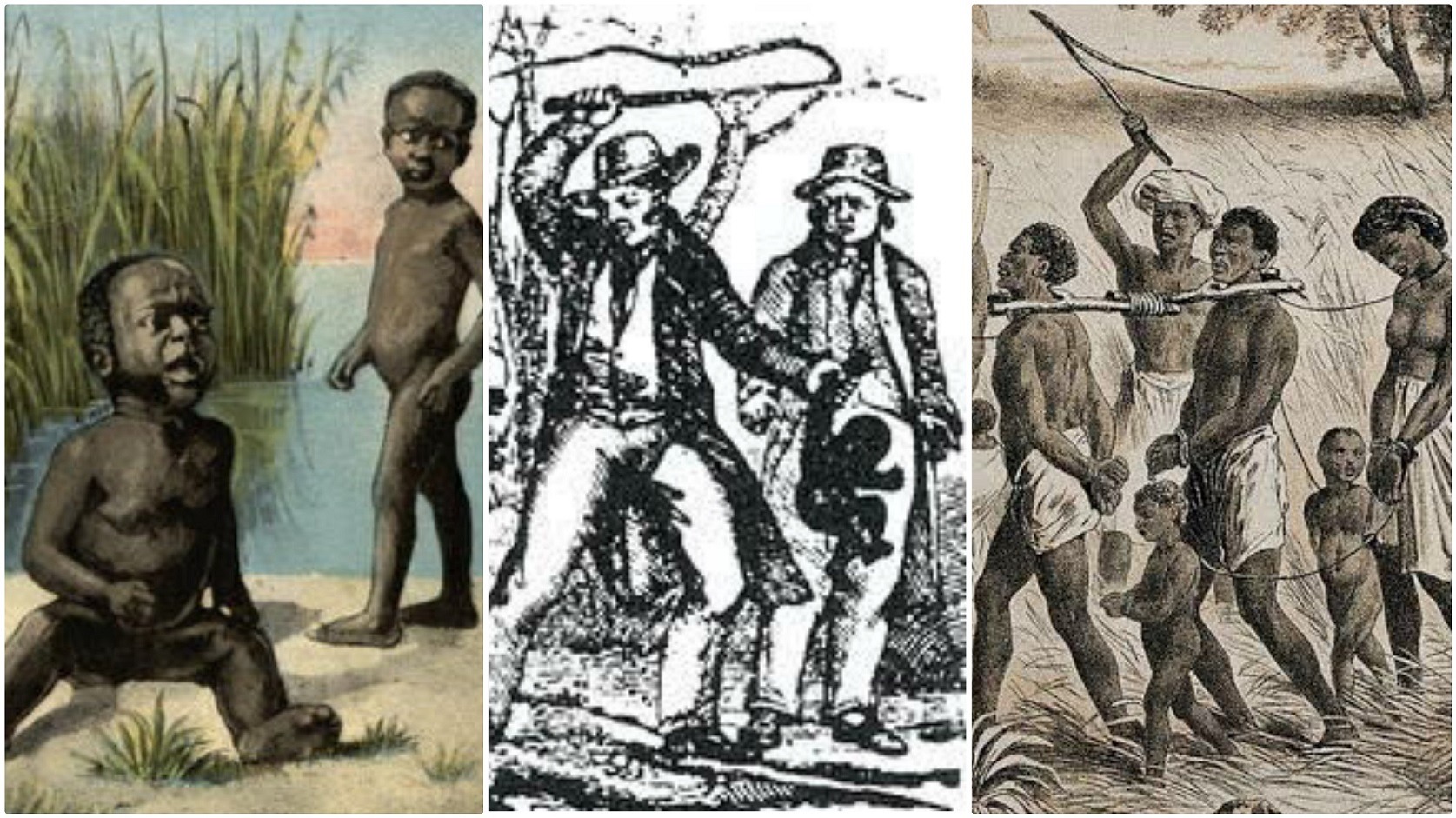

“Despite strict regulations, voodoo was one of the few areas of unlimited autonomy for African slaves.” It was a source of psychological liberation as a religion and a crucial spiritual force because it allowed them to express and reinforce that self-existence they objectively acknowledged via their own efforts…

Voodoo also allowed slaves to psychologically break free from the very real and literal ties of slavery and consider themselves as independent creatures; in essence, it provided them a feeling of human dignity and allowed them to survive.”

How Voodoo Became Haiti’s Predominant Spiritual Practice

David Geggus writes in Marronage, Voodoo, and the Saint Domingue Slave Revolt of 1791:

“Haitian voodoo, along with other Afro-American faiths in Brazil and the Caribbean, is one of the most spectacular manifestations of neo-African culture in the Americas.” The slave trade to Saint Domingue (now Haiti) ceased more than a half-century before that to Brazil or Cuba, and Haiti did not have the post-slavery interaction with Africa that brought the Shango and Kumina cults to Trinidad and Jamaica.

However, the huge proportion of Africans in the country’s population when the French were exiled in 1803, as well as the country’s prior and post-expulsion religious traditions, help explain why voodoo became the majority religion of Haiti. In the 1790s, Africans made up well over half of the non-white population. “Efforts to Christianize the black populace were negligible between the expulsion of the Jesuits in the 1760s and the end of the schism with the Vatican in 1860.”

Dutty Boukman’s Voodoo Instigated A Revolution

“The god who created the earth; who created the sun that gives us light. The god who holds up the ocean; who makes the thunder roar. Our God who has ears to hear. You who are hidden in the clouds; who watch us from where you are. You see all that the white has made us suffer. The white man’s god asks him to commit crimes. But the god within us wants to do good. Our god, who is so good, so just, He orders us to revenge our wrongs. It’s He who will direct our arms and bring us the victory. It’s He who will assist us. We all should throw away the image of the white men’s god who is so pitiless. Listen to the voice for liberty that sings in all our hearts.”

Boukman’s Prayer from the ceremony at Bwa Kayiman

According to The Louverture Project, “Boukman (also Boukmann, Dutty Boukman, or Zamba Boukman) was a leader of the uprising in its early phases; he is reputed to have performed a vodou ceremony at Bois Caman on August 22, 1791, which heralded the start of the rebellion.”

He had traveled from Jamaica to Saint-Domingue, where he had become a maroon in the Morne Rouge jungle. “grotesque-looking man… with a ‘awful countenance,’ a visage like an overdone African carving,” says the author. (P. 39, Parkinson) He was a fearless and inspiring leader.

While Boukman was not the first to organize a slave uprising in Saint-Domingue, as others such as Padrejean in 1676 and François Mackandal in 1757 had done before him, he provided the spark that helped to ignite the Haitian Revolution. “Boukman Dutty (dubbed “Book Man” in Jamaica because he could read) was sold by his British owner to a Frenchman (his name was changed to “Boukman” in Haiti). He was a Vodou priest, a giant with imposing presence and courage to match, with undeniable authority and command over his followers, who known him as “Zamba” Boukman.”