The Fourth of July is not really something I observe ~ Arielle Gray

Growing up, I was never particularly moved by the beautiful fireworks display or the historical studies in school about America’s independence. The cookouts with meats sizzling on the grill and the festive atmosphere of sharing meals with relatives I haven’t seen in weeks are what I find most thrilling about this time of year.

In school, the American History curriculum included a sizable section on the history of Independence Day. I studied and memorized the major figures in the American Revolution and was provided with a typed copy of the Declaration of Independence nearly every year so I could prepare for quizzes and exams. However, no one ever brought up Frederick Douglass’ renowned essay “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July,” which criticized the holiday’s revelry, during my time in school. Perhaps the spirit of resistance and revolt was only pertinent when it came to how America won its independence, not to how America achieved and maintained its power — through the rod and whip of slavery.

My grandfather, an active man who made it a point to introduce me to the black culture at a young age, first exposed me to Douglass’ speech. I don’t fully recall the last time I went with him to hear “What to the Slave Is The Fourth of July” recited, but I do recall how I felt. I was aware that I wasn’t suited for the Fourth of July.

READ ALSO: The Famous Frederick Douglass Speech – What To The Slave Is The Fourth Of July?

In 1852, Douglass delivered the ground-breaking “What To The Slave Is Fourth of July” speech to the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society at Corinthian Hall in New York. He condemned America’s independence, saying that it had little significance for the slaves who were still working in the American South. Up north, free black individuals continued to struggle with a structurally racist culture and lacked any legal safeguards against housing discrimination, segregated educational institutions, or even physical harm. “I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us,” Douglass said in his speech. “I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us.”

The play “What To The Slave Is Fourth of July?” exposed the hypocrisy of a country that was so anxious for independence yet so unwilling to grant the same liberties to the slaves who were the backbone of the economy. Asserting that slaveowners were using the Bible to defend the enslavement of slaves despite the fact that the sacred text highlighted everyone’s right to freedom, Douglass also cast a critical eye on the church. In his opinion, the church in particular could have a significant impact on the abolition of slavery.

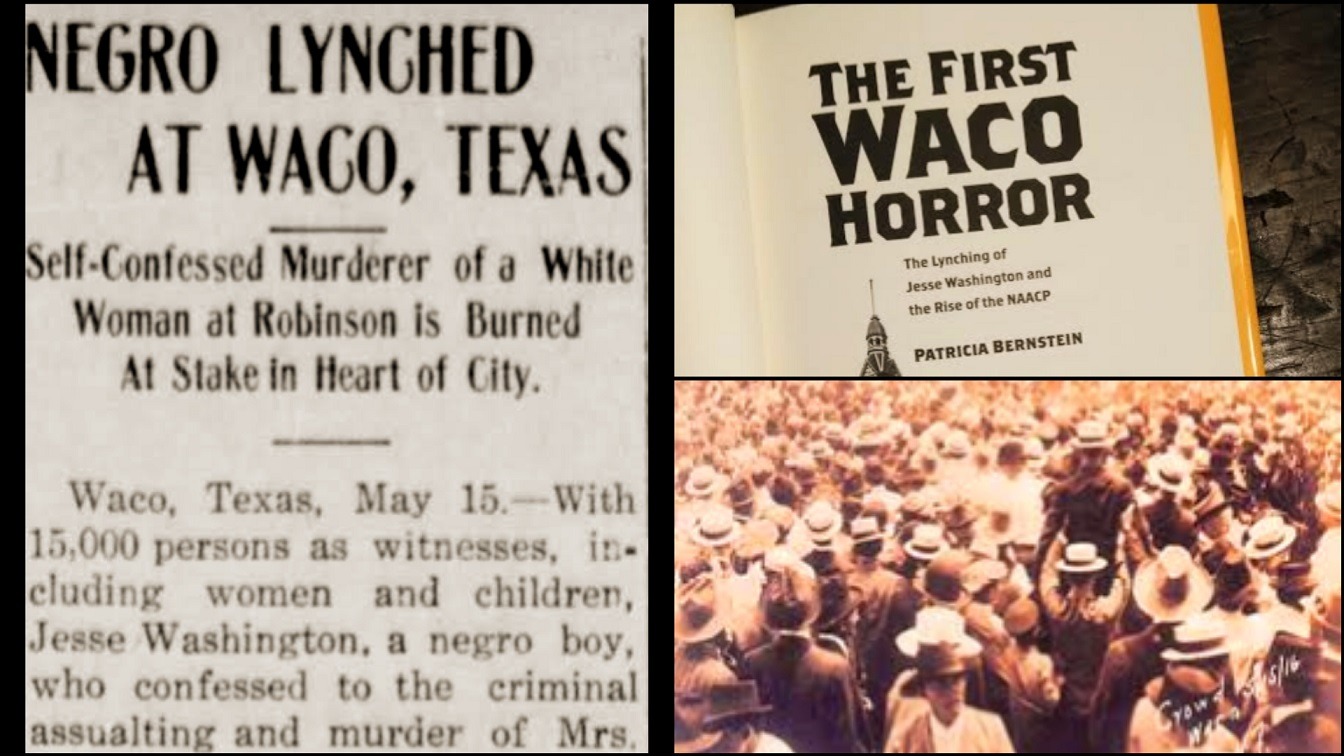

Before Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, eleven years had gone since Douglass’ speech. The last enslaved individuals in Texas did not hear that they were free until 1865. But freedom and independence remained false, meaningless concepts long after slavery was abolished.

Douglass’ message still holds true today, just as it did back in 1852. There is a purpose to the speech’s annual recitation by groups in the Boston area the week before the Fourth of July. The political environment we are in right now clearly reflects how our nation views freedom. Your freedom is a possibility, not a given if you are not white.

The Fourth of July is marked by pomp and ceremony, which includes numerous free musical performances, fireworks displays, and other themed events.

What is the Fourth of July to us when the same freedoms it is supposed to protect are routinely violated by the government? What does the Fourth of July mean to us now that our freedoms are merely temporary and prone to change? What exactly does the Fourth of July represent? Does it have any meaning? Or is it just a hollow promise?

“The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me,” Douglass said in his speech. “…This Fourth of July is yours, not mine.” His assertions are ones we must meditate on when the time comes to pull out the fireworks and light up the grill when it’s time to head down to the Esplanade to watch the lights explode over the Charles River.

I wasn’t able to make it to the yearly reading of Douglass’ speech in Boston Common this year, and I’m not sure if my grandfather and I will ever go again. But the lesson I learned along with him all those years ago is still relevant today. For us, the Fourth of July still represents a phony declaration of freedom that is often just a mirage. It continues to be a meaningless festival with no soul. And each year we are reminded that even if we can attend the party, it isn’t for us. We are merely guests who could or might not be asked to leave after the celebration is finished.

This piece was originally written by Arielle Gray, arts engagement producer for WBUR