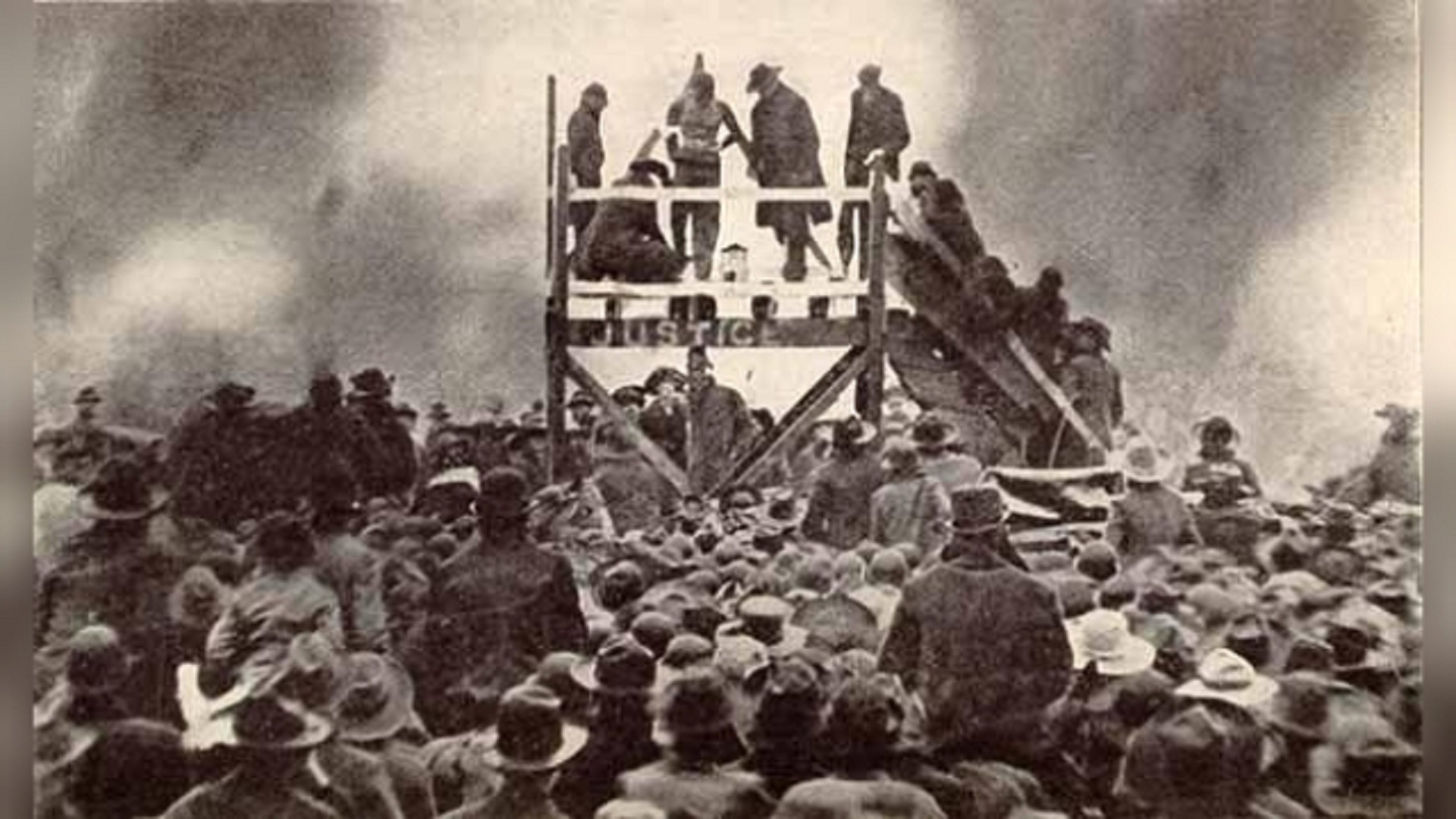

The Lynching Of Henry Smith took place in front of an estimated 15,000 onlookers in Paris, Texas, on February 3, 1893. His death was one of the earliest documented public lynchings. Ida B. Wells, a journalist, and anti-lynching activist was struck by the heinousness of Smith’s execution. In her groundbreaking essay The Red Record, which sought to expose the injustices of racially mob violence, she offered a full account of the incident.

Myrtle Vance, a four-year-old white child and the daughter of Henry Vance, a Paris police officer, was killed by Smith. On January 27, her body was discovered in the woods near Paris. Many Paris inhabitants thought Smith was inoffensive and feeble-minded, so he supported himself by working odd tasks at the homes of local whites.

Despite his outward appearance, his interactions with the child’s father appeared to make him an obvious target for suspicion. Several days before Myrtle’s death, Henry Vance, a guy known for his rage and abuse of inmates, had arrested Smith and assaulted him for disorderly behavior and intoxication. Some locals believed Smith had committed the crime against Myrtle in retaliation.

Smith went to Detroit, Michigan, after learning that he had been designated a suspect, and then boarded a freight train bound for his prior location in Arkansas. Smith may have felt he might find refuge in his previous hometown. He was apprehended more than a hundred miles from Paris in Hope, Arkansas. The news of Smith’s planned homecoming quickly circulated across Arkansas and Texas. Because no trial was planned, citizens of Paris rapidly publicized the date and hour that Smith would be tortured and burned.

5,000 people awaited Smith’s return to Paris when the train taking him to the station in Texarkana arrived. He was placed on a platform (like a float in a procession, according to others) that took him to a scaffold built near Paris with the word justice emblazoned across the front. 15,000 onlookers eventually gathered at the scaffold, with men, women, and children straining their necks and straddling other viewers in order to have a clear view.

Vance’s relatives stood with Smith on the shabby wooden platform, cutting his clothing from his body piece by piece and tossing the pieces to the throng as keepsakes. They then slashed his torso with hot iron rods, forcing them down his neck and into his eyes. After that, he was drenched in oil and set ablaze. Smith shrieked in pain. Smith attempted to flee the platform as he and the coals beneath him began to ignite and fell 10 feet to the earth. Members of the mob lassoed him and lifted him back into the fire.

Texas Governor Stephen Hogg, outraged by the lynching, sent a telegram to the Sheriff of Lamar County the day after Smith’s burning, urging that those involved be imprisoned. No one was ever arrested for the torture and murder of Henry Smith, despite the governors’ pleas for justice and the public nature of the crime.

A gang of white men hanged Smith’s stepson, William Butler, in adjacent Hickory Creek, nearly two weeks after his death for allegedly suppressing information about Smith’s whereabouts. Butler’s killers were never brought to justice.

![Black Man Who Designed Washinton DC and Invented The Clock [Benjamin Banneker]](https://libertywritersafrica.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Black-Man-Who-Designed-Washinton-DC-and-Invented-The-Clock-Benjamin-Banneker.jpg)